The UK Is Coming for Your IP

Another OA proposal wants your IP without just compensation — this time in the UK. Resistance is quick and strong.

Hot on the heels of yesterday’s post about “the government funding lie” — the notion that if the government funds any part of an activity, they own all the production from that activity — we have similar nonsense coming out of the UK based on who you work for.

The new Research Excellence Framework 2029 (REF29) has been released, and it is proving rather unpopular with UK academics, especially those in the social sciences, because it cuts off commercial opportunities in a draconian and (I would assert) illegal fashion via uncompensated “takings.”

From what I can tell, in the UK, laws about eminent domain and compulsory purchase revolve around the same central issue as in the US — the government can’t simply take something from a private interest (citizen, business) without adequate and fair compensation. That means they have to pay for it, and determining the amount to be paid is a process.

In the UK, there are also processes around compulsory purchase including the property owner’s right to object to the purchase and/or the amount given as compensation. Again, there is a process for this.

All these processes are in place to ensure that compulsory purchase and claims of eminent domain are made only when necessary, and that the rights of citizens and private enterprises are respected and upheld.

Unfortunately, woolly-headed academic OA advocates don’t seem capable of doing their homework or looking outside their own cloistered world before making pronouncements that defy law, custom, and common sense.

Call me surprised . . .

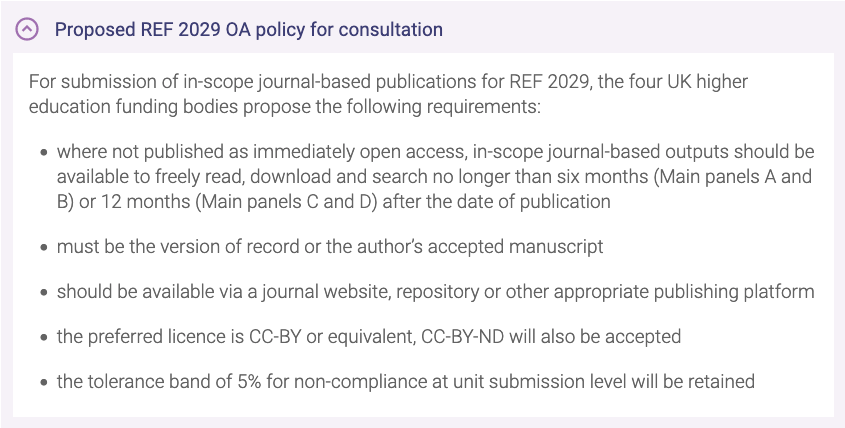

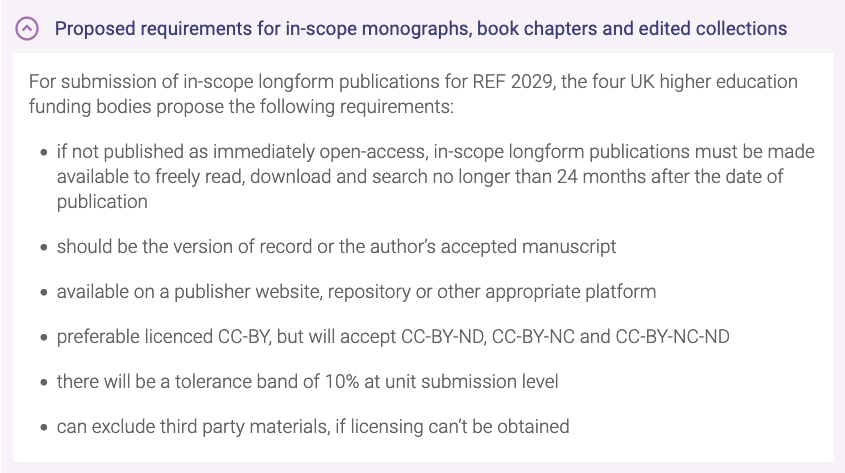

There are two main parts of the REF29 land grab — one for journals, and the other for books and monographs.

It’s no surprise that academics in the social sciences would be most upset about this. They write some fantastic books that can sell for years, if not decades. But the same goes for professionals in the medical and hard sciences, with grants sometimes providing the time and headspace needed to produce a good book tying together disparate themes.

As for journal articles, like it or not, these are private property. First, the authors claim copyright. These are typically private citizens. (US government employees producing research as part of their jobs — e.g., CDC scientists — can’t claim copyright, but this is a sensible and well-known exception that proves the rule.) While there may not be much if any commercial upside to the publication of their articles, they are still private property. When (and if) copyright is transferred to a publisher (or a perpetual license is granted), those are transactions between two private entities. It is none of the government’s business. Grants don’t buy them blanket rights, and even signing over rights to get the grant is something to think twice about.

But some out-over-their-skis bureaucrats who have snorted too much OA fairy dust seem to think they can boss citizens around. Just recall this lovely bit of hubris and overreach from the Social Security Administration as part of their response to the OSTP guidance (bolding mine):

All scientific research publications and scientific research data resulting from our federally funded research will be our property with unlimited rights to reuse, reproduce, and make available at any physical, digital, or online location accessible to the public.

We may require unlimited rights licenses to use, modify, reproduce, release, or disclose research data in whole or in part, in any manner, and for any purpose whatsoever, and may authorize others to do the same, depending on the facts and circumstances of the award.

In the UK, there’s a lot of pushback against these aspects of REF29, with one academic writing:

Normal commercial academic publishing is being murdered by this nonsense, but hey, who cares, right?

On top of this, government bureaucrats are attempting to go around laws regarding compulsory purchase or eminent domain by claiming that involvement with an academic institution or grant-making entity gives them power over private citizens, essentially making these citizens who accept grants a specific form of indentured servants — you have to work off the grant by surrendering your rights and any commercial opportunities having those rights might have provided.

Antipathy toward a commercial marketplace is at the heart of the OA movement, even though a thriving commercial marketplace produces health competition for quality, provides academics with direct or indirect income, and creates jobs in related fields that support science, research, and societal good.

- What the OA movement and its reliance on the APC model has done has been a disservice to the marketplace, causing it to consolidate into a few, major hands, while decimating the non-profit publishing space.

- In Australia, there is handwringing over the amount spent on publications, yet the proposed solution is . . . more OA. It’s as if these people don’t know what they’re doing.

When a government believes it can seize the work of private citizens without fair processes, adequate compensation, or even a defensible rationale (yes, OA doesn’t really make sense — prove me wrong, as isn’t the world getting better as the percentage of articles published OA has increased?), we have lost our way.

It may be time to call the lawyers . . .