AI, Music, and Perverse Incentives

Music streaming services are fooling around with playlists to boost profits and marginalize artists — and MIT's empty D2O boasting

Last December, Jason Farago wrote in the New York Times:

I remain profoundly relaxed about machines passing themselves off as humans; they are terrible at it. Humans acting like machines — that is a much likelier peril, and one that culture, as the supposed guardian of (human?) virtues and values, has failed to combat these last few years.

Humans in the music industry seem to be acting more and more like machines.

AI songwriting programs like Suno are finding it easier to mimic human voices because humans have applied auto-tuning technologies for years now, making it trivial for computers to hit so-called “correct” pitches with what they generate, and to have that sound “normal” to us.

We made our voices robotic, and that in turn made our expectations robotic.

The cyborgunation goes both ways.

Due to streaming services, algorithms, and revenue sharing, music is increasingly beset by AI and perverse incentives, with humans adopting and adapting to these tools and techniques in order to make money — while not caring about the music.

In scholarly publishing, we’re also participating in a similar degradation of cultural contributions for the sake of catering to algorithms and the incentives they currently create, as I wrote about back in January:

Touting OA is our world’s effort to justify feeding the machines, while gatekeepers, editors, theorists, thinkers, and individual contributions are denigrated, overwhelmed, and sidelined.

More on an unexpected possible offshoot of this tomorrow . . .

But back to the music industry, an interesting cognate in some ways.

Spotify is the dominant streaming platform. Artists receive royalties from documented Spotify plays. The more music that is streamed while commanding royalties, the more it costs Spotify to operate. Ipso facto, if Spotify can fill its playlists with music that doesn’t require paying an artist any royalties — or, at worst, dramatically reduced royalties — Spotify can carve a path to profit.

This appears to be an active operational strategy, as Ted Gioia and others have documented.

In one case, a composer named Johan Röhr has used 656 different pseudonyms to populate 144 playlists on Spotify with 62 million followers and achieving 15 billion streams. Röhr is 47, has created more than 2,700 songs on the platform under pseudonyms like “Maya Åström,” “Minik Knudsen,” “Mingmei Hsueh,” and “Csizmazia Etel.” His private company reportedly pulled in 32.7 million kronor ($3.13M) in 2022. All his songs are short instrumentals.

Like other artists engaging in the same practices, Röhr apparently lives just down the road from Spotify’s headquarters, leading some to speculate that these artists are in cahoots with Spotify in some way — perhaps running a workshop making AI-generated and ambient music to clog playlists with songs for a flat rate, or at a reduced royalty, in order to help Spotify achieve profitability.

The songs do not have organic popularity. You’ve certainly never heard them outside of Spotify, or would want to. They’re pablum. In one case, a song that has received 6.5 million streams on Spotify has just 65 plays on YouTube.

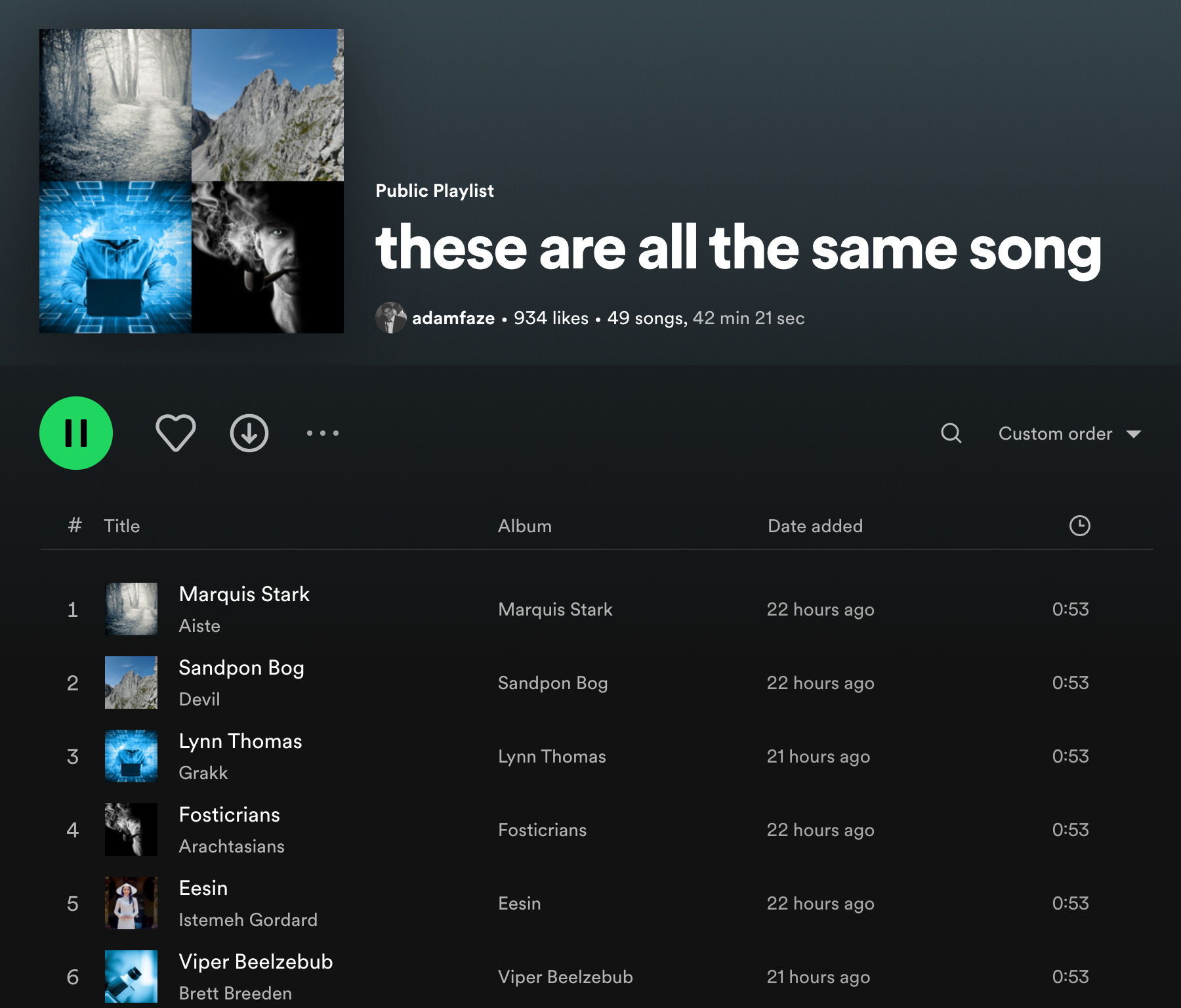

They also aren’t all different, except in their metadata. Adam Faze, an IT specialist, has documented 59 iterations of the same song on Spotify by 59 different “artists.”

He created a 49-song playlist of the clones, and another user found 10 more iterations of the same song by different people soon after.

Calling these “Potemkin playlists,” Gioia’s speculation is that Spotify and other streaming platforms are creating these to avoid paying royalties to original artists.

- It’s not Spotify’s only effort to avoid paying royalties. It is being sued in the US for attempting to pay lower royalties by claiming the addition of audiobooks to its offerings makes it a “bundle” operator, whereby it can pay lower royalties.

It’s not just Spotify. Apple Music and others have been found pitch-shifting classical music and changing the artist’s name, platforming the resulting music as royalty-free originals. Musi, a popular streaming service making more than $100M since January 2023, has achieved the same end by simply not paying royalties.

As to the attempt to reduce royalty payments by peddling “Potemkin playlists,” one industry insider said:

The songwriters and producers of these tracks are either paid a fixed fee per track or a combination of a low advance and reduced royalty rate, and it works because these “labels” can guarantee millions of streams through their own network of search engine optimized DSP playlists and YouTube channels.

The role of AI in all of this — from generating artist names and song titles to generating the music itself — is unclear, but speculation is rampant that AI is generating music that’s being published, and is sure to become more prevalent, if not dominant. Sony Music Group has issued a letter warning more than 700 companies against using its data to train AI.

- As mentioned above, a site called Suno allows anyone to make AI-generated songs, which are bad enough musically, while the lyrics are atrocious and often hilarious.

Spotify’s approach is vertical integration at its worst, because, as Gioia writes:

. . . the biggest problem on the web today is that the dominant platforms have shifted from serving users to manipulating them. But unlike some other free web platforms, Spotify has tens of millions of paying customers. It’s one thing to manipulate people who are using your service for free — you might argue that they get what they’re (not) paying for. But how should we feel about a world where you pay money every month, and still get deceived and manipulated?

Ultimately, this ties into the flattening of culture, as streaming services seek to privilege unoriginal, repetitive, ambient, and filched music in order to drive profits, while original artists struggle, are marginalized, and have fewer options for meaningful discovery and distribution.

The Digital Gilded Age continues as technologists exploit the creative class to line the pockets of a handful of billionaires.

It’s the story of our time.

The MIT Press D2O Boasting

Speaking of perverse incentives, MIT Press is boasting that their Direct2Open (D2O) books are receiving 3.21x as much use and 20% more citations, citing this as evidence that OA books work better.

Once you get past the OA activism, however, the picture becomes much more nuanced and even downright unclear.

For instance, the comparator set isn’t delineated, and could simply contain books in subject areas that are less mainstream, authors who are less well-known, or subjects that at the moment aren’t supported by the broader culture (e.g., when The Queen’s Gambit was hot on Netflix, books on chess were all the rage).

But making the boast and attributing it to access doesn’t make sense even using the sparse data they share. It turns out that 3.75% of the titles accounted for ~27% of the usage they cite in the report, an indication that access modality is not what is making the difference, but rather the subject matter and relevance of what is being published. There may even be titles in the set that are underperforming those in the putative comparator set.

And that comparator set is not clear at all, as online usage of MIT Press books has to be rather difficult if they are not OA — at least as far as my sampling could determine. Maybe institutional licenses are different, but even then, we don’t know the penetration of these licenses, or how primed for SEO the non-OA books are.

There is also no mention of sales, despite the hardcover of the most downloaded book being for sale on Amazon, via the MIT Press site, and with an e-book for sale for $1 less than the hardcover via Penguin RandomHouse. In fact, all D2O books are for sale elsewhere, but heaven forfend they boast about D2O boosting retail sales — or admit that D2O hurts retail performance. Why tell the whole story when the narrative you’re after is all about OA?

Did the OA-available books sell more copies than those not made available in this manner? Is there also a commercial upside? How did they deal with “double-dipping” perceptions given the funding of D2O alongside commercial sales?

Given how difficult it is to find the OA version of the book using on-site navigation or otherwise, I’m guessing most of the “usage” is transient discovery via search, with no real indication of how engaged in the content users have been. Was it a click and trash experience? Or, did it help drive commercial sales?

We can’t know via the kind of usage data touted here.

It seems predictable/tiresome and weird for a university press to be pushing an ideology about publishing, especially when it’s simultaneously pushing commercial sales while pretty much misrepresenting the data to support a preconceived narrative about a lane of access politics that is losing its luster.

Maybe what this report truly shows is that that 96% of the D2O titles generate very little interest, requiring them to use averages to obscure an entire portfolio’s overall mediocrity, and leveraging data that are highly skewed as a transparent marketing head fake.

The OA silliness is strong with this one . . .