Can You Retract from an LLM?

Atomized, tokenized, and weighted, papers may not be addressable anymore

Our recent podcast discussion of the “double bubble” faced by scientific publishers — OA and AI — caused me to finally try to address a question that’s been on my mind off and on:

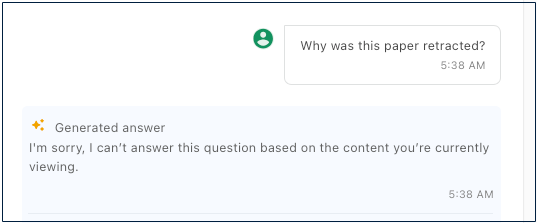

- Can a paper be retracted from an LLM?

Let’s look at two LLMs in medical publishing used by two top medical journals — NEJM’s “AI Companion” and OpenEvidence (which adds JAMA, among others) — to gauge an answer.

Bottom line? Expect the unexpected.

Let’s dive in.

This post is for paying subscribers only

Already have an account? Sign in.