Externalizing Our Cognitive Work

Open data backfires, while scholarly publishing unilaterally breaks its social contract

Most people have a lot of rituals — which side of the bed they sleep on, when and how they brush their teeth, even where they store their food and the brands they buy.

Habits and rituals do a lot for us, mainly by alleviating cognitive burden.

It takes a lot of effort for humans to think in a conscious manner. We find it more natural to let our limbic brains do the driving, so to speak — and even literally. If you’ve ever driven somewhere familiar without incident but also without any clear memory from the drive, you’ve been driving without cognitive burden.

Cognitive burden is easy to spot once you’re attuned to it, and probably accounts for a lot of the stress of the pandemic, as we’ve had to consciously refactor so many things previously handled within habit and ritual.

We naturally shed cognitive burden as we learn. For a simple example, if you’ve gone for a hike someplace new, the way to the turnaround point seems to take a lot longer than the hike back, even though the distances are the same. Your brain gets to relax on the way back, ticking off a few familiar landmarks and the general lay of the land while you traverse the return. Your cognitive burden is lower already, as you’ve learned the path.

Our desire for “a new normal” is partly a desire to alleviate cognitive burden. We want to know which habits to keep and which we can drop, so we can stop thinking all the time — about masking, mandates, Zoom calls, our spouse in the house, and so much more.

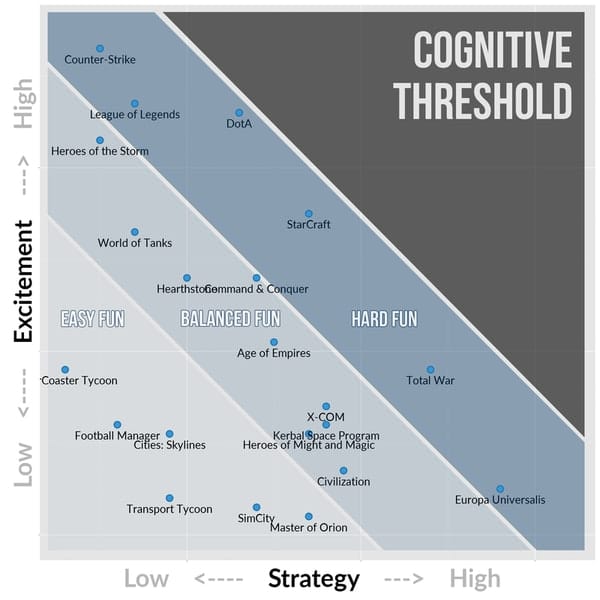

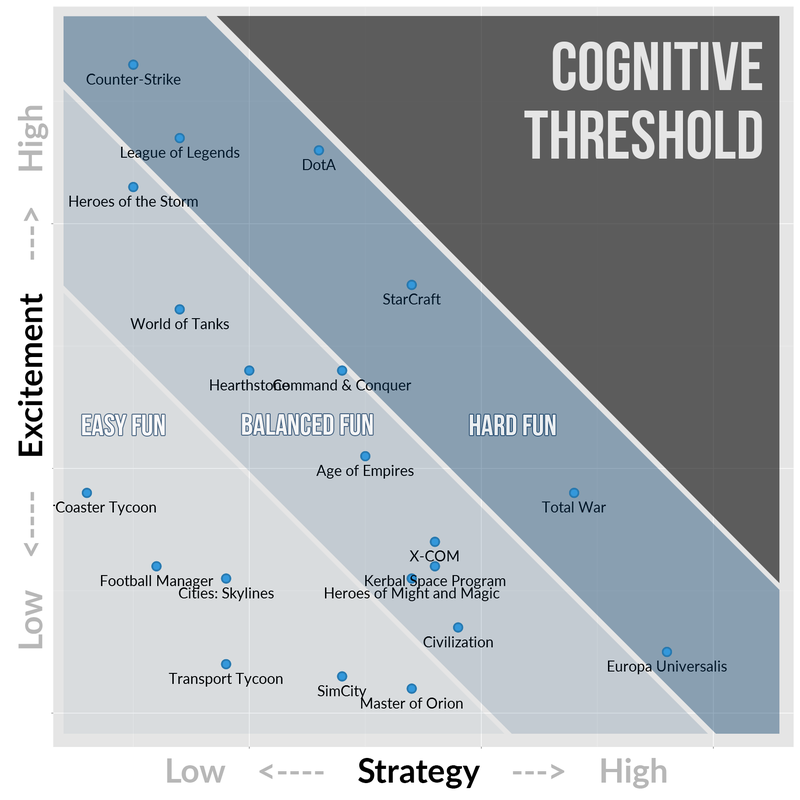

Game designers know these concepts well, up to and including the cognitive threshold — the point at which people shut down and walk away, unable to process what’s going on and retreating for their own protection.

We are now in an information environment that imposes cognitive burden as a matter of principle. We used to fret about friction, neglecting to think about the cognitive burden of managing 2-3 screens at once. Newsfeeds popularized by social media are designed to push readers toward a cognitive threshold, and many people go briefly over the edge when they try to find something that appeared just moments before. Some simply refuse to back away, not realizing a dopamine habit is pulling them over their personal cognitive cliff.

Cognitive burden is at the heart of the kind of exhaustion I talk about when it comes to performative publishing, like preprints and other open science and OA approaches. We once inherently prided ourselves on eliminating cognitive burden, and worked hard to make articles concise, abstracts structured, data presentations instructive, and papers better and more relevant. This made sense to me as a pragmatist, for whom it’s clear that most people don’t want to have to think about these things, but rather want to know what to do and what an expert thinks. Now, I can hear the “information wants to be free” types gearing up their “you’re so condescending” objections, but let’s get real — it’s what most busy professionals and you want, too. After all, you and nearly everyone else have better things to do than sort through thousands of preprints and scads of csv files. You want someone to do it for you, and you’re willing to pay for it.

Think about it this way — Do you really want to spend the time necessary to think about whether your crackers are safe and don’t contain poisons? Do you really want to have to spend hours evaluating fuel or electricity mixtures using touchy lab equipment before you fuel or charge up your car? Do you really want to figure out the best logistics for getting your package from the warehouse to your front door?

No. You want someone else to have figured out all of that — and to ensure consistency — for you, so you can eat crackers, get someplace safely, and receive your packages without having to think about more than the flavor of the snacks, the price of the fuel, and what you want to buy.

The same should go for information, especially scientific information.

Publishing and editorial jobs involve shouldering a high level of cognitive burden to alleviate it downstream. Editors and publishers reject submissions that are wrong, irrelevant, or inadequate, refine things that have merit, and publish things that appear very likely to be correct and to advance science and knowledge. It’s fantastically interesting work, but it is difficult if you do it well and in good faith.

It’s especially important to do such work when some people are purposely trying to exhaust us, amplify nonsense, increase our cognitive burden, and push people across the cognitive threshold into emotional, angry, and unreasonable beliefs.

Dealing with these malefactors may mean less open information.

In a major plot twist I haven’t seen others write much about, some governments are removing data from the public square because responsible people are realizing the risks of putting it all out there in an environment of deception and distortion. The dream of “open data” is proving more dystopian than anticipated, much as the dream of “open access” has already proven.

What do I mean? I’ve been monitoring the liars and fraudsters recently enabled on Substack, and let me tell you — life in the Land of Conspiracies isn’t pretty or pleasant.

It is emotional, with enemies lurking around every corner and in every office. The writers try to overwhelm the minds of readers, exhausting reason and rationality by overloading people. Their process is about pushing people across a cognitive threshold.

Mundane descriptions of scientific limitations become full-throated conspiracies. Terrible tragedies are exploited without care for either the goodwill of those examining the underlying factors and trying to untangle cause and effect, or for the families and individuals affected. Brutal, careless, and rampaging, such writers exploit the trust people instinctively place in media sources in order to deceive people.

And what do we get as a result? People who no longer think clearly.

And data pulled out of the public square.

Last month, Public Health Scotland decided to stop publishing its weekly data on Covid infections because the data were being misused by anti-vaxxers and right-wing medical theorists. The data are complicated and highly nuanced, but if you elide these complexities and nuances, you could make them tell a different story — which is what the conspiracy theorists naturally did.

The best remaining solution? Take the data down.

The CDC decided to withhold data for similar reasons last month, with the complexity of the data, its preliminary and incomplete nature, and difficulties with interpreting it cleanly contributing to the caution. As Diana Cervantes, director of the MPH Epidemiology Program at the University of North Texas Health Science Center at Fort Worth, said:

Not providing an interpretation of the data will definitely lead and has led to misinterpretation of data. Any organization that collects, analyzes, and intends to disseminate information should never forget to interpret the data clearly and for the audience it is intended for.

Interpreting data for an audience reduces cognitive burden for that audience.

These stories raise the question of whether putting such data out in the first place served any useful purpose. Can any open science advocate think skeptically enough to consider this possibility? That more is not better?

Life always provides some cognitive dissonance, so to fulfill this requirement, these events occurred around the same time as the NIH issued a “seismic mandate,” according to Nature News — a data-sharing policy for all funded research.

So, governments with experience posting open data are pulling it back, while the NIH plows forward, likely to learn the hard way that sharing data isn’t all it’s cracked up to be.

For more cognitive dissonance, Springer Nature and Research Square celebrated more than 530 journals tossing preprints out into the winds, joining others (notably, Preprints at the Lancet, which populates itself with desk rejects) in conduct that inevitably increases the cognitive burden for others, while enabling conspiracy theorists.

What will it take for us to return to a more pragmatic information management system, one not built on vague ideologies and vacuous beliefs about provably false (at this point) cause-and-effect arguments?

As Scotland and the CDC are reminding us, interpreting the data for the intended audience is essential, and it requires careful work.

These aspects don’t occur to those promoting open science, because serving others through thankless hard work isn’t what it’s about — quite the opposite, it’s more performative and vainglorious, as I wrote last December:

We now have enough evidence that wading into “open” has done nothing its advocates claimed it would, because it has a fundamental flaw — “open” has become synonymous with “I, as a researcher, can do whatever I want, and expect you to serve me.” In that mode, “open” becomes a version of lazy entitlement, as if having a PhD or MD or Master’s degree means that other people have to attend to a variety of Ivory Tower whims.

It’s rewarding to serve others, and that means exhibiting a duty of care, which means remaining humble, remembering we all have feet of clay, behaving as responsible members of the communities we’re part of, and seeking the truth. “Me, me, me” is not congruous with any of the above, but it has become the modus operandi of open.

There’s an “I” in “science,” but that’s only because of how it’s spelled.

Shrugging off and externalizing the cognitive burden of grappling with claims, data, and interpretation isn’t scientific and scholarly communication to me. But I can see how it degraded. Pushing PDFs out after a sniff test is a comparatively easy job, and if the pay is the same, why not? I’m not that cynical, but many are. It is a shame, however, because there are people involved with open data, OA, and preprinting who have the chops and work ethic to do so much more, and their talents are being squandered in a period where it’s stylish to externalize the work they should be doing.

Meanwhile, there’s no getting around that simply opening up information is a form of abdication, and an abrogation of our responsibilities.

It’s also a trick. People think we’re doing the job assigned, while we are shirking our responsibilities and pushing our culture toward cognitive overload when it comes to science. We haven’t told people that we’ve decided they need to do the jobs we used to do, which ultimately erodes trust in us and science, as it becomes clear that we’re not willing to do the work to craft reliable information. Would you trust a retailer that didn’t seem to care enough to provide safe and reliable food, fuel, or shipments? Would you trust any other industry that allowed this?

How does abdicating our role benefit us or science in the long run? How does making science a burden instead of a guide help society and the people in it?

The Geyser — Hot Takes & Deep Thinking on the Info Economy is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.