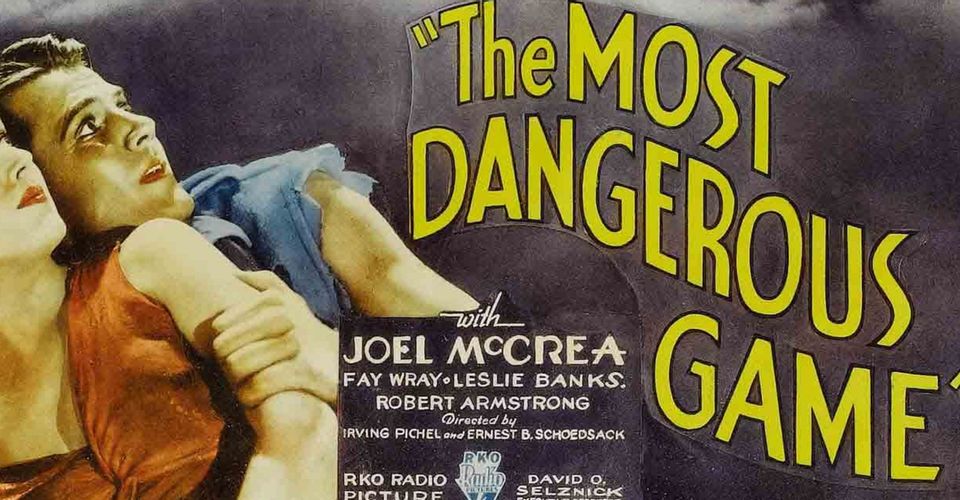

QAnon — A Game Playing People

Game dynamics are being leveraged to draw people into Q's alternate reality

QAnon is a misinformation force so potent and compelling that some compare it to an emerging cult or religion. It peddles in dangerous fictions, mostly centered on power, liberal politicians, and bizarre conspiracies about pedophilia and human trafficking. It helped fuel the conspiracies behind Pizzagate, and has far too many people believing Kamala Harris trades in human body parts, Joe Biden has dementia, or Donald Trump is a hero taking on all evils. AM radio and churches are underappreciated sources of QAnon influence, which usually originates online.

In September, a game designer using the nom de plume RabbitRabbit offered an interesting perspective on why and how Qanon works. With Qanon playing perhaps a larger role than anyone was able to discern in the recent US elections — including the election of the first overt QAnon candidates — his insights seem worth elaborating here, even if they’re not precisely on topic.

RabbitRabbit designs live-action role playing games (LARPs), alternate reality games (ARGs), and experience fictions (XFs). These types of games allow participants to enter into compelling fictional universes written with amplified good-evil stakes, perceptible narrative thrust, and assorted clue trails. Dinner party mysteries are the most familiar example.

To outline a key concept QAnon and such games share, RabbitRabbit recalls one of his first XF games, where he created a basement game for participants. He thought it was super-easy, with obvious clues bound to lead to a quick solution. Unfortunately, the participants saw three stray wood chips on the floor that looked to them like an arrow pointing toward a wall, and began to attack the wall with tools, convinced this was a clue. They wouldn’t look at anything else once they fixated on the scraps of wood the designer didn’t even realize were there.

This perceptual trick is called “apophenia,” and is the tendency to perceive meaningful connections between unrelated things. In this case, it ruined the game, and taught the designer a crucial lesson:

These were normal people, and their assumptions were normal and logical and completely wrong.

This is an important point when it comes to how surprising it can be when you discover someone in your life is susceptible to QAnon conspiracy theories despite being otherwise trustworthy, nice, and kind. They are all those things, but they are also completely wrong, because they are being played without realizing it. As the designer continues:

. . . in real games there are actual solutions to actual puzzles and a real plot created by the designers. It’s easy to get off track because there is a track. . . . QAnon is a mirror reflection of this dynamic. . . . QAnon grows on the wild misinterpretation of random data, presented in a suggestive fashion in a milieu designed to help the users come to the intended misunderstanding. Maybe “guided apophenia” is a better phrase.

Flooding the zone with random and contrived information becomes a virtue for QAnon, given these factors, as the designer notes:

Every cloud has a shape that can look like something else. Everything that flickers is also a jumble of Morse code. The more information that is out there, the easier it is to allow apophenia to guide us into anything.

While QAnon leverages elements of game design, it is not a game because it’s not being made for fun, even if it can feel fun. It has a purpose, and that purpose is to spread chaos in a manner that serves Q, the imaginary leader of QAnon.

The fiction of Q is itself part of the game, and cycles are wasted speculating on who it might be — a disaffected national intelligence official? Donald Trump?

But just like the all-powerful alien in Star Trek: The Next Generation, Q is a contrivance, a character. As the game designer notes:

Q is not a real person, but a fictional character. QAnon uses the oldest trope of all mystery fiction. A mysterious stranger shows up and drops a strange clue leading to long hidden secrets which his clues, and your detecting power, can reveal. . . . Q is a “plot device.” Q is fictional and acts exactly like a fictional character acts. This is because the purpose of Q is not to divulge actual information, but to create fiction.

The way the QAnon fiction is propelled along involves Q urging followers to “do your own research.” This kind of participation invests players in the QAnon game, and lays the groundwork for much of the rest of the manipulation, elements RabbitRabbit lays out logically and sensibly:

- Follow the breadcrumbs. QAnon followers are urged to track every small clue or breadcrumb, with the effect that the resulting ideas become their ideas. If you generate an idea, you’re prone to defend it. “If we ‘create’ the ideas in our own minds, they become fused much more intently into our personality. They’re OURS.”

- Demonizing the mainstream media. Another important reason for propagandists to get people to “do the research” is to instill a natural distrust for society and the competency of others. “The conspiracy plot always has the same logic. The reason no one knows about the conspiracy is because of the conspiracy. Not because it doesn’t exist. Then initiates are given the tools to arrive at ‘their own conclusions’ which are in every way more compelling, interesting, and solve more problems than traditional conclusions. Because they are wrong and fictional.”

- The QAnon community is fun. “Solving puzzles together is a great way to form community and to join community. . . . If Q drops some clues, then you have something to do and you have people to do it with. It’s bonding. The same reason puzzles are used in corporate teambuilding exercises and party games.”

The Medium post gives examples of how QAnon uses imagery and other “clues” that are faked or forced to provide players with a rewarding game experience.

RabbitRabbit also touches on why objective review of scientific findings sets science apart, along with the culture and goals of science, explaining to some degree the tension between the fictional version of “do your own research” and the responsible, enculturated, and purposeful version of it:

. . . the difference between apophenia and science is just the scientific process and the reliance on proof. People make the connection before they know for a fact if it’s real or not. Maybe it is apophenia, maybe not. It’s a hypothesis. A theory. THEN YOU TEST IT. The facts determine the outcome and then, whether it feels good or not, you accept them. Even scientists may not want to let go of a good theory that just isn’t panning out. The feeling of correctness is over-powering. This is why people need to have peer-reviews. Colleagues need to be able to replicate results. Solutions need to be tested and the facts harnessed.

In Q, the proof is more apophenia! Another arrow in the dirt in an endless cycle back to the central propaganda. It has to because there is no truth. The answer is whatever feels the best, makes the most sense, and helps the story. Any truth is just fuel for the propaganda and reinforces the conclusions of the apophenia and central narrative.

Even QAnon seems to know it’s a game, disavowing the label again and again with TINAG (“this is not a game”) thrown out quite frequently. Making sure it’s not perceived as a game is vital for it to work. As RabbitRabbit explains:

Knowing what is “in game” is a huge priority of game designers and players alike no matter how life-like the game. . . . People call the actual police if they think there is an actual crime, so your players have to know they are playing a game, or else. . . . Of course, again, this is the opposite of the stated purpose of Qanon. TINAG is literal.

Like many people I spoke with this past week, I was alarmed to see more than 70 million fellow citizens voting for an incumbent President who has fouled things up in so many ways, and who represents what I think are our worst natures. But then I heard some stories about how people I know and love have been fooled by QAnon, and also how an underapprectiation of QAnon may explain the polling errors and other surprises around the election.

As RabbitRabbit notes, QAnon is exploiting elements of human nature we have come to terms with in other ways:

How easy is it to live in a fantasy world?

Pretty easy actually. Love, civilization, honor, good/evil, religion, money, etc. What is real and what is a fiction that we have created and agreed to live as if they existed? Maybe you don’t believe your religion is a fiction, but what about everyone else’s? Are they all equally real?

Being able to share and believe in our fictions, acting on them as if they are real, may even be one of our evolutionary advantages.

The entire post is worth reviewing. There’s a lot more to learn from it, and from related posts from others who are also convinced QAnon is an malevolent ARG.

I found this elaboration of “QAnon as a game” quite compelling. It explains a lot of how and why people get seduced into it, embrace the manipulation, defend the ideas they glean from it to the high heavens, and become distrustful of others in a way that seems to make them happy.

Shutting it off? That may take some demystifying subversions. Anyone want to help me design, “QAnon — The Dinner Party Mystery Game”?