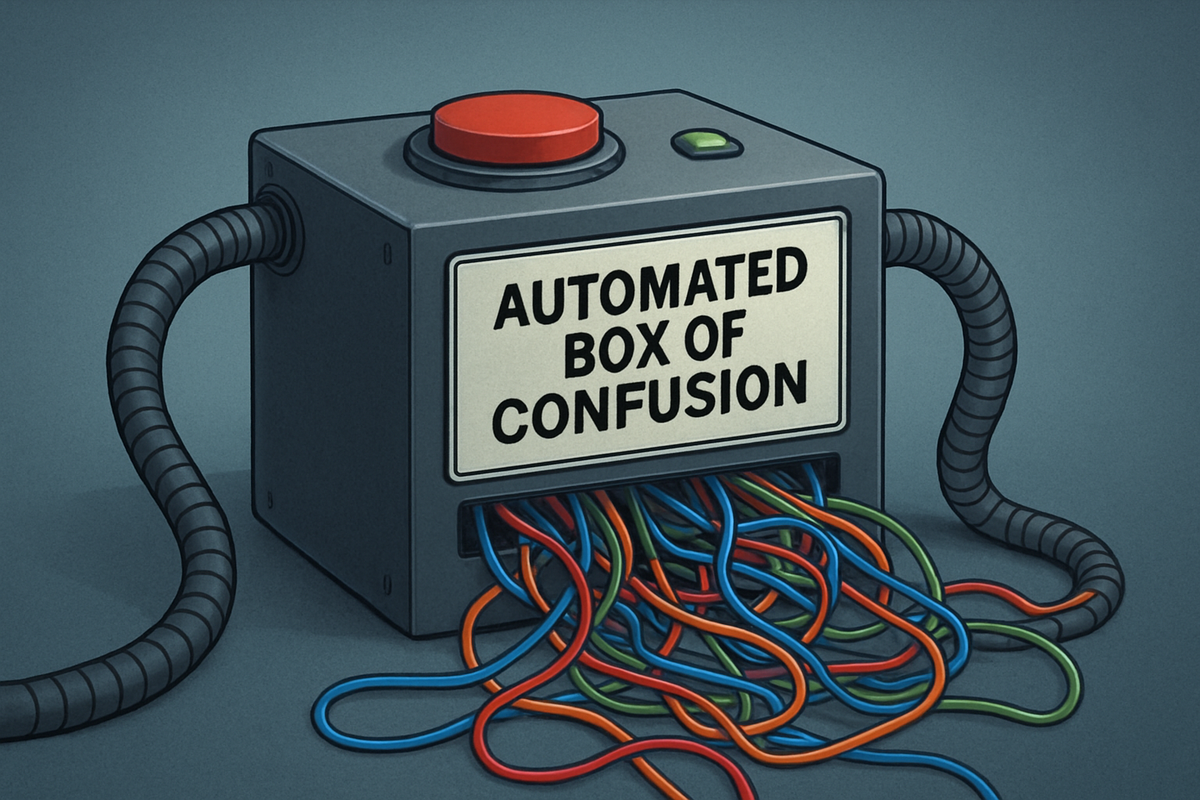

The “Automated Box of Confusion”

Cut for space from our forthcoming book, it’s a concept at the heart of it all

It has gained new relevance as the paper in question is now under public scrutiny as flawed research, which allowed for scare-mongering of the public by the authors.

This describes how scientific publishing’s digital landscape now celebrates technical speed and scale at the expense of scientific relevance, quality, and care.

In chasing tech, we spaghettified our dissemination technology, creating what we think of as an “automated box of confusion” around each scientific claim. These days, most of the best journals unwittingly activate it every time they publish, while dodgy journals exploit it. If publishing is a button, it’s one that activates a freakish network cascade that would make Rube Goldberg blush.

To trace it as best we can, let’s look at an OA paper published in February 2025. The authors paid the publisher — Nature Medicine — an APC of $12,690 to make the paper OA. The paper claimed to show that we each have a plastic spoon’s worth of microplastics in our brains. It was widely covered in the media, with the lead author making the spoon comparison when he spoke with reporters. A significant correction to the paper was published in March 2025.

But the February 2025 paper wasn’t the first version available, or the first version the media covered. The first publicly available version was an unreviewed preprint posted nine months earlier (May 5, 2024). It was posted to the preprint server Research Square, which is associated with the ultimate publisher of the paper (Springer Nature). It was posted one week after the paper was submitted to Nature Medicine as part of the publisher's “In Review” system, a node on the box of confusion.

But this was not really the first appearance of the preprint. An author proof of the Research Square-branded preprint was posted on ResearchGate, the article-sharing site, on April 30, 2024, nearly a week earlier. It was indexed by Google that day.

The May 5, 2024, preprint on Research Square was indexed the next day in PubMed, with the full text of the preprint published on PubMed Central (PMC) and Europe PMC at the same time. This automatically created a linked publication event at NIH.gov for the work and availability in a half-dozen automated feeds using varying protocols (FTP, AWS, etc.).

To recap — within one week, a draft paper just submitted to a journal and probably only beginning its review process had been posted on:

- ResearchGate

- Research Square

- PMC

- Europe PMC

- NIH.gov

- The PMC Article Datasets feeds, available via FTP, AWS, HTTP, and other formats for unlimited download and reuse

These versions received 460 media mentions, and the unreviewed preprint was cited 27 times. The preprint was also indexed for discovery via search in ResearchGate, Research Square, PubMed, Europe PMC, Semantic Scholar, and Google Scholar, along with public search engines like Google.

Remember, this is one unreviewed paper, one unvetted scientific claim. There are thousands of scientific papers published every day on average. The “automated box of confusion” had done all of this for thousands of papers without anyone lifting a finger.

When the paper was officially published in February 2025, it received 790 media mentions and 34 citations by mid-May. Of the 1,250 total media mentions of the claims, more than one-third were to an unreviewed manuscript posted by the authors without any substantive external vetting or evaluation. Coverage of the peer-reviewed version occurred nearly a year later.

In March 2025, a month after the peer-reviewed paper was published in Nature Medicine, a correction was issued. This correction was substantial, including revised figures, corrected math, and new figures. However, by this time, the media had moved on. The correction received no media coverage. The multiple preprint versions carried no notice of the correction, and were not updated.

While the paper was considered problematic for scientific reasons, we’ll focus on the way the scientific publishing system created a cat’s cradle of versions, feeds, linkages, and posts. Even for this single paper, there is no longer a version of record (VoR) that is unmistakable, a clear entry in the scientific record. There are no clear signs of the care and caution around scientific claims one might expect.

Quite the contrary. The lead researcher’s institution issued a press release where he was quoted saying, “The findings should trigger alarm,” despite writing in the paper, “These data are associative and do not establish a causal role for such particles affecting health.” All of this has been done to no apparent benefit to science or society. With current incentives in a swamped information environment, fear-mongering to attract attention and strut for further grants is the norm, even if it creates alarm where none is needed.

Let’s consider a different reality, as if this article had been published within the community of environmental health experts without all the public feeds and OA versions. It would likely have found its natural place as a contribution to the scientific record within that community — good, bad, or indifferent. The public may or may not have gotten involved. Instead, by being pushed to the public via OA and multiple feeds and discovery tools and clumsily warped to gain the most attention, it may have done more harm than good.

What began as, “Let’s see what the Internet can do” has become — especially after being given the Gold OA transactional business model and what metastasized off that — “Let’s see what we can do with the Internet.” All too often, we see people posturing for grants (best case), seeking to exploit others, or trying to create false narratives. Their techniques include fear-mongering, bad faith dives into open data, the creation of false data, the publishing of fake journals, and the construction of false narratives. And then we try to mount inadequate efforts to catch bad information after the fact.