Using ChatGPT

ChatGPT is a new AI agent released late last year by OpenAI. It has been hyped by some as the next level of AI, possibly capable of passing the Turing Test someday.

It has a distance to go if that’s the goal, because right now it’s insufferable.

In my experiments with ChatGPT, I found it to be one of two things — good enough that I wanted to actually have a conversation with it, to clarify or dispute a couple of points, or too wordy and waffling, incapable of delivering a synthesized answer, and therefore a boor.

For example, when I asked it, “What is peer review?” the answer was quite good, if too long, and there are points I would have liked to have discussed:

Peer review is a process by which experts in a particular field of study or practice review and evaluate the work of their colleagues before it is published or presented. The purpose of peer review is to ensure that only high-quality, accurate, and relevant work is disseminated to the broader community. Peer review can be used to evaluate research papers, proposals, grant applications, and other types of academic or professional work. It is an essential part of the scientific and scholarly publishing process and is meant to improve the quality and integrity of published work. Peer review helps to ensure that research findings are reliable and trustworthy, and it helps to identify any errors or weaknesses in the work.

You can ask ChatGPT to regenerate its answer, and its second answer was a little tighter and less debatable:

Peer review is a process in which a work, typically an article or manuscript, is reviewed by a group of experts in the same field as the work being evaluated. The purpose of peer review is to ensure that the work meets the standards of the field and is of sufficient quality for publication or presentation. Peer review typically involves several stages, including the submission of the work for review, the selection of reviewers, the review process itself, and the final decision about whether to accept or reject the work.

When asked something philosophical, ChatGPT often picks up on pop culture elements that match the question, such as when asked, “Why do fools fall in love?”

"Why Do Fools Fall in Love" is a popular song that was first recorded by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers in 1956. The song has been covered by numerous artists over the years and has become a classic of rock and roll. The lyrics of the song ask the question “why do fools fall in love?” and suggest that love is a mystery that can'’ be explained. The song does not offer a definitive answer to the question it poses, but rather invites listeners to consider the many different ways in which people fall in love and the various factors that can contribute to the formation of romantic relationships.

Pretty joyless.

That’s not to say that ChatGPT isn’t interesting. The language model is quite smooth and good, but there’s something wrong somewhere else, underscoring that our own sensory, nervous, mental, and memory systems are far more complex than anything yet sculpted from silicon.

The joylessness continues when ChatGPT is asked to do something creative. For instance, you can direct it to write a song in a certain songwriter’s style, and it comes back with dreck. So, I asked ChatGPT to write a song in the style of Tom Petty. Here are some of the lyrics it came up with:

Verse 1:

I was feeling down, my world was upside down

I didn't know which way to go

I was lost in the dark, couldn’t find a spark

I thought I’d never see the light

Chorus:

But then you came along, like a ray of sunshine

You showed me the way, and now I’m feeling fine

You picked me up when I was feeling low

You’re the one I need, you’re my Tom Petty song

No sense of rhythm, bad rhymes, clumsy internal rhymes, unimaginative wording, and then to actually end with a reference to the song itself? Oh boy.

Compare what ChatGPT generated to some actual Tom Petty lyrics:

It’s alright if you love me

It’s alright if you don’t

I’m not afraid of you runnin’ away, honey

I get the feeling you won’t

Say, there is no sense in pretending

Your eyes give you away

Something inside you is feeling like I do

We said all there is to say

Even though ChatGPT writes lyrics like a precocious 3rd grader, its output is a little impressive, and a little worrisome when it comes to the current off-loading and conditioning trends for human creativity and consciousness.

Those are the stakes here.

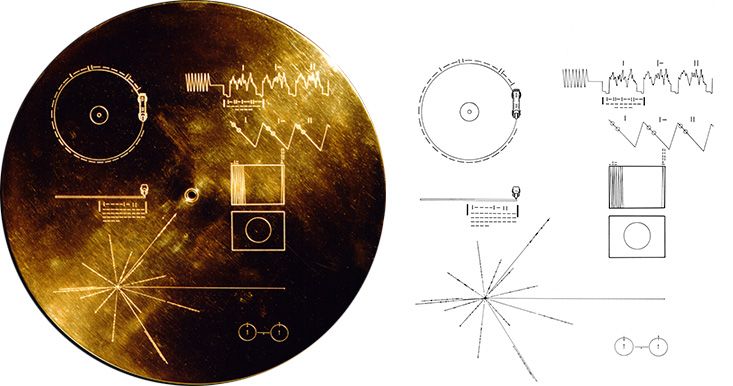

Rick Beato published a great video yesterday outlining how music — one of humanity’s central creative activities, so much so that we sent some of our favorite songs out into space on a gold record via Voyager so that any intelligent life could hear some of our favorite tunes — is gradually being changed by computers. The most important part of his discussion is how humans are being conditioned to accept computer-modified music — computer-corrected pitch, rhythm, and even enunciation — creating a precursor to computer- and AI-generated music as the new standard and norm. One example shows a single sustained note by Billie Eilish having been edited in more than 80 areas to sculpt and craft the final note we hear, and Eilish is an excellent singer. What is actually recorded when Eilish sings? A demo track for the computer to use? Where are we when the distinctiveness, vibrato, and resonance of a natural human voice starts to sound foreign to us?

Or when a scientific finding is generated by a computer that has an audit trail but no fear of death or shame?

And when computers are set loose to create songs at whatever clockspeed they can muster, the potential for the song market to be flooded by millions of songs — and for human artists to be displaced by computer music labs that are happy with billions of pennies from meaningless yet soothing EDM loops — is real.

What does Adele do when the market doesn’t have room for “35”?

The crux of the matter — whether the topic is music, reference works, scientific knowledge, or societal advancement — is whether ChatGPT represents progress for humanity, an advance for computer technology and AI, or both.

If it’s not both, then what kind of price might humanity pay as AI changes our perceptions of the world and our role in it? Does AI actually get us beyond where we were without it, or do we simply have to lower our expectations of ourselves to create room for it? Does it make us more active and creative? Or more passive and derivative?

Are we just a species that references the past and listens to pleasing tones? Or are we adventurers, explorers, thinkers, creators, and storytellers with ingenuity and inventiveness?

ChatGPT and things like it ask us to reassess who we are as a people and as a species. Maybe it will help us shake off our lethargy when it comes to the encroachment and coddling of tech, and make it so we actually have to compete with millions of annoying 3rd graders who are rapidly evolving into pretentious, computer-generated college freshman songsmiths with perfectly tuned air guitars and equally pat and reductive world views.

Game on.