With Loneliness, It’s the Little Things

A survey appears to confirm we miss small moments of recognition and connection

In 2018, the UK announced its Minister of Loneliness.1 Japan announced their Minister of Loneliness last week. Loneliness has been a defining trend of the 21st century so far — from Robert Putnam’s 1995 book “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community” to the past year of few hugs, no handshakes, and scant incidental encounters, the world seems to be conspiring to separate and isolate us. Even our smartphones and social media have turned into divisive, isolating phenomena.

In 2018, a survey by Cigna found loneliness in the US to be “at epidemic levels.” A 2017 survey of women found they feared loneliness more than a cancer diagnosis. Loneliness has negative health effects, including chronic inflammation, heart disease, and Alzheimer’s.

But thanks to capitalism, you can “rent a friend” in some cities, and “rent a family” in Japan. Most of those who take advantage of these services are professionals who don’t have time to make real friends or form real families.

Last week, “The Geyser” conducted a survey about professional and personal loneliness and isolation, receiving 93 responses. I cover the results and comments below.

This all came to mind after an an eye-opening interview last week, in which author Noreena Hertz discussed her new book, “The Lonely Century: How to Restore Human Connection in a World That’s Pulling Apart.”

Sad fact after sad fact about loneliness and isolation came out:

- 20% of Millenials say they don’t have a single friend — not one

- Isolation and loneliness are hurting women more than men, and major setbacks in the workplace for women stemming from the pandemic — which have pushed employment levels back 30+ years — exacerbate it all

- Loneliness in the workplace is increasing, and can occur even when people appear to be interacting — if someone’s ideas or opinions aren’t respected or acknowledged, they can feel even lonelier and more isolated

- Virtual work and schooling have made us and our children lonelier still

- Addiction to smartphones and social media have made us feel alone — even when we’re in the same room

Since the Internet came on the scene, it’s been making us more isolated from one another, our eyes on a screen or heads facing down. The lack of eye contact you encounter when you look for it is striking.

Worse, the infrastructure of robust, in-person social lives is being dismantled and defunded — from movie theaters to libraries, gyms to restaurants, clubs to community centers. Many have closed or become harder to locate and use. Funding for public libraries has fallen 40% since 2008, for example. When we don’t rub elbows, natural empathy fails to emerge.

We’ve been doing it to ourselves via the habits of what is supposed to be a great age of connection — by streaming movies at home and listening to music in our noise-canceling headphones. We’ve been killing our own social opportunities, choosing take-out over eat-in, Amazon over our local hardware store, and a quick liquor store run over a nearby watering hole. Abundance itself works against us — we rarely watch the same shows, making even our entertainments isolating.

Isolation can come with success, as one person commented in our survey:

“There is a loneliness that comes with management. The higher up you go, the more isolated [you become]. This is independent of COVID effects. For me it’s been important to foster a group of peers that I can share with. But this is delicate too, as some of the peers work for competing businesses, limiting what one can share.”

Loneliness can be political. When entire slices of the population feel unseen or unacknowledged — in the US, people in the Midwest, or racial and ethnic minorities, or young people, or women (who have been disproportionately affected by job loss and isolation during the pandemic) — you can have widespread disassociation that manifests in suicide, drug abuse, or insurrection. Some politicians try to sow divisions.

Isolation makes us more psychologically vulnerable. Add in QAnon and exploitative media, and you get people believing all sorts of nonsense. Divided we fall.

Isolation can become a vicious cycle, if we lose the skills of connection, discussion, banter, and revelry. When we lack some abilities to participate and support one another in an inclusive democracy as citizens who are circulating and therefore more naturally empathetic toward one another, we start to see distrust and unease.

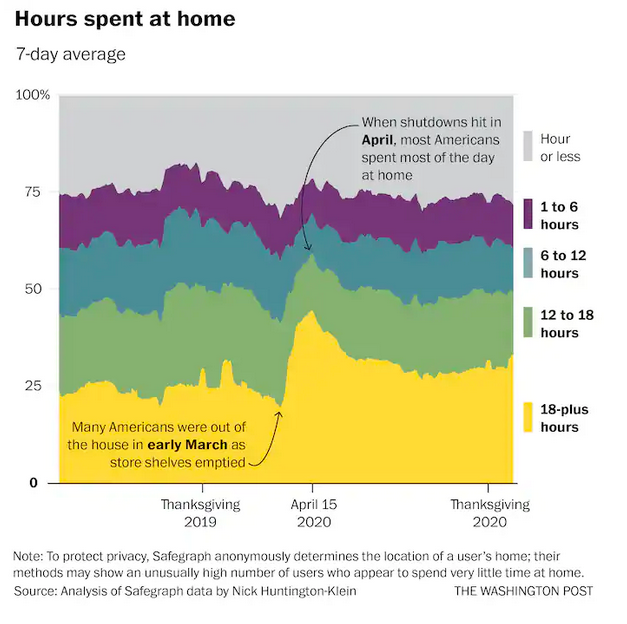

For a variety of reasons, we were getting lonelier before the pandemic — and that was when we had workplaces, restaurants, gyms, bars, and movie theaters to go to, and no major worries about airborne communicable disease. Now, it’s been a year of increased isolation. A recent report in the Washington Post illustrates how when the pandemic hit, most of us began to spend the majority of our time in our homes:

As a few people commented in our survey about the lack of real-world interactions:

“Physical isolation has massively exacerbated my feelings of professional isolation.”

“It’s easy to tag co-workers on Teams and video chat anytime, but it doesn’t replace in-person conversations. . . . The in-person meet ups usually left me inspired and invigorated.”

“. . . within the society I work for, virtual seems to be increasingly less considered a valid substitute for meetings — we notice significantly lower interest and many challenges compared to in-person meetings. . . . A large majority of people . . . [are] looking forward to meeting in-person again.”

How are people in scholarly publishing and communication faring? According to our survey, they’re doing better in their personal lives than in their professional lives — and as a group, they’re doing OK overall, based on average scores:

- Feeling professionally lonely or isolated — 45 out of 100, with 0 = “Never,” 50 = “Sometimes,” and 100 = “Always”

- Feeling personally lonely or isolated — 42 out of 100, with 0 = “Never,” 50 = “Sometimes,” and 100 = “Always”

- 42% have led activities intended to blunt loneliness or isolation at work

- 38% have participated in activities to mitigate loneliness and isolation at work

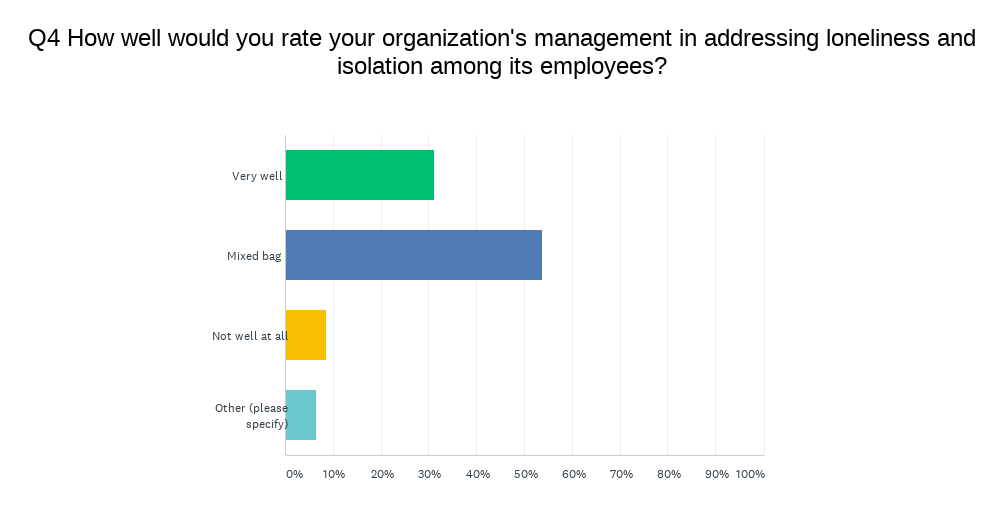

- Management is mostly rated as a “mixed bag” at addressing these issues:

“While our HR send out ‘well-being’ updates every now and then since the pandemic started, relative to things being done for friends by other companies my employer is lagging behind on stimulating virtual interactions. There’s also a constant ‘we must save costs’ mantra to respond to the pandemic and its impact on company finances — so staff are having to work harder covering roles for which recruitment is frozen.”

- Weekly meetings and project meetings are providing the most connection for people, with 74% reconnecting during weekly meetings and 67% benefiting from project meetings

- Texting and messaging finished third at 63%

- Every form of connection listed as an option on the survey was used by more than 50% of respondents — everything seems to help

Based on comments, what many people seem to miss the most are those small, unexpected, and affirming interactions we once danced through during our days with ease. Hertz calls these moments “micro-exchanges” — the 30-90 second interactions with servers, cashiers, managers, staff, coworkers, strangers, and acquaintances. Psychologically, these can be more important to feelings of belonging than longer exchanges with more intimate connections.

It was easy to find thoughts about such things in the comments in our survey:

“A strong work culture of being friendly and informal (sending jokes, memes, general chit chat, etc. interspersed with work chatter) has helped me weather this immensely.”

“I worry the isolation will have/has had a significant effect on the ability to converse with people. Already I avoid phone calls and have trouble making small talk in shops.”

“. . . lately I’m forcing myself to call instead of just sending email . . . because then we can exchange pleasantries, judge moods, etc., a lot better. I know this is management 101 stuff, but worth remembering . . .”

“The lack of informal interaction with colleagues at work is starting to take its toll. The inability to grab a cup of coffee with a friend is devastating.”

“I feel much less connected to the staff who report in to my direct reports. I used to chat with them at their desks and in hallways. I miss staff swinging by my office to ask questions or check in.”

“I think what I miss most in general, not specifically tied to work, is incidental social contact. I work from home anyway, but it’s all those daily social interactions from a chat with the person at the register at the coffee shop, to a comment made at the grocery store, to more extended conversation at the car service center, to some idle conversation at a conference, that add up in the course of a day or week and have all been subtracted. Everything now is so intentional — it’s scheduled, has a defined beginning and end, takes place in the same location — I think what is really driving my increasing sense of social isolation is the loss of the impromptu.”

Some people are finding the new ways perfectly compatible with their personalities and preferences, however:

“As an ambivert living with my spouse and children coupled with an organization that has taken this subject seriously, I have struck the right balance that I feel well connected and could continue on this way in the long term if needed.”

“On a personal level, I’ve really enjoyed the lack of forced social gatherings over the past year. I don't think I’ll ever say yes to a get-together with people I only kind of know or kind of like anymore. I’m very grateful for that silver lining. The past year has made me much more aware of how I’d like to spend my time, and making idle small talk is not it!”

While true and valid — as a wise man once said, “Extroverts never understand introverts” — small talk and unplanned interactions provide many people with necessary social ballast. In an essay called “The Year Without Friends” by Amanda Katz, she writes [bolding added]:

What is gone? Serendipity: We are less likely to run into each other at a party or even on the street and tell each other notable new facts about ourselves and our mutual friends. Situational proximity: Unless we’re in essential roles, we zoom in for meetings but don’t overhear our coworkers reacting to good or bad news and lean over to make sure they’re okay, nor do we spill out of a class and decide to go have a drink and a chat with a classmate. And physical intimacy: We rarely have one of those long walks or late-night hangouts with friends where at a certain point we feel comfortable enough to move from the superficial to what’s really on our minds. For many of us, those face-to-face encounters are where the important work of friendship is done.

Perhaps we’ll end with this thought from a survey respondent:

“Loneliness and isolation comes from having a primarily inward perspective. If you face outward, think about those around you, you see how many people are facing the same challenges and that alone can create a sense of community, that we're all in this together. Reaching out and offering help or just saying hi increases that sense of community tenfold. Community and neighborhood apps can play a large role in that, and can lead to more professional connections. It may sound trite, but we really are all connected in some way.”

Thanks to everyone who took the time to respond to the survey. We are social animals, and collaboration of all kinds — virtual, in-person, team-based, and 1:1 — needs support for us to feel included, recognized, and supported.

And give the introverts their due. Assumptions that socializing is universally pleasurable can be misleading.

This was created after Theresa May’s government accepted the findings from the Jo Cox Commission on Loneliness. Cox was a UK politician who was murdered by a far-right extremist while at a meeting with constituents.