Why MAHA Is Better at Comms

By unifying a message into theater, the right continues to dominate communications

The Internet has changed the pecking order of outlets. What was for decades a reliable hierarchy of traditional media — the New York Times, network News, a major medical journal, and local TV, radio, and newspaper outlets — has fragmented into far more personalized channels shaped by algorithms.

Over time, these algorithmic outlets have coalesced most clearly at the right-wing political end of the spectrum. FOX News played a major role, ensuring a steady stream of politically tilted resentment theater. Social media found the recipe, tasted the results, added some ketamine and jet fuel, and created a set of new right-wing media darlings, some of whom are now running the US government.

These new outlets and their talent are running circles around everyone else in the comms space, getting the messages out, sowing seeds of discontent about science and scientists, and moving the public into alignment around artificial dyes, pesticides, organic food, “biohacking” ideas, and vaccine dangers. They know the game, with one major player using “Scicomm” to describe his efforts to fog the mirror of nature:

It’s working, too. A recent survey found that the public approves of RFK Jr.’s core MAHA agenda, with up to 90% agreeing it should be easier for average Americans to understand food safety guidelines.

This is a good example of how being good at comms can mean you’re good at propaganda because it stems from one of the core complaints of MAHA — “the food pyramid” and all its problems:

MAHA thespian after MAHA thespian complains about the food pyramid, their underlying gripe being that it’s hard to understand and outdated.

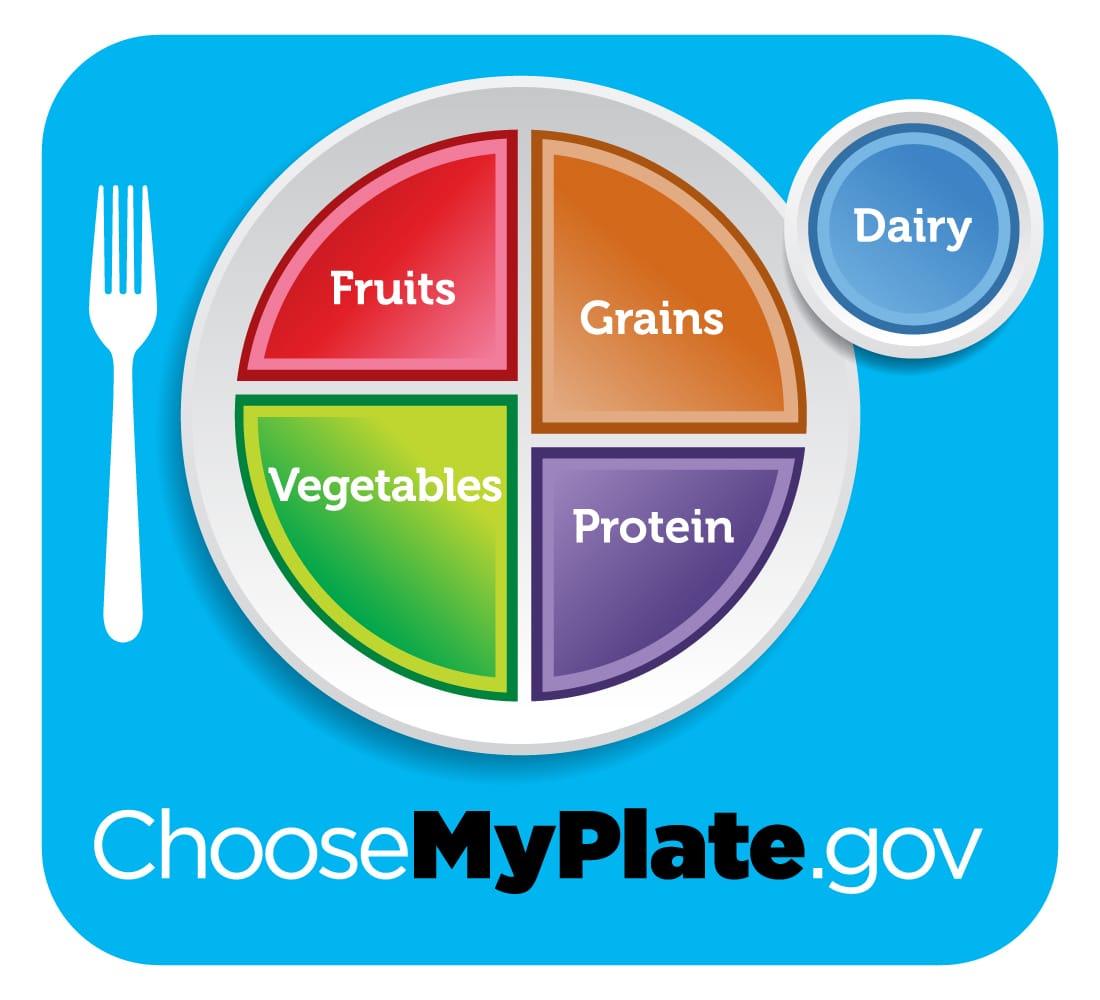

Maybe that’s why it was replaced by “My Plate” in 2011:

MAHA acolytes don’t seem aware of this, and focus on beating the dead horse of the food pyramid.

This signals two things:

- MAHA people are reactionaries. Their information and complaints are from a prior era, and they want to return to those eras to fight old fights they didn’t get to fight then.

- MAHA is so much better at comms it creates backdrafts. Most of us don’t know “My Plate.” The USDA came up with a smart, sensible update to the Food Pyramid, but most of us don’t know about it, use it, or share it with our kids. MAHA is so good at comms that they are accidentally making us aware of “My Plate” by causing a reaction among nutritionists, while showing how bad at comms the public health workforce has been in the age of algorithms — probably because algorithms don’t like uncontroversial information.

MAHA theater — what I’ll call “political fiction science” or “gaslight science” — is built for the footlights, not the floodlights, so don’t look too closely. When you do, the pancake makeup jumps right out . . .

What does this mean for publishers? How do we communicate better?

“Open” is not the answer. It is passive and weak. We keep hearing about efforts to make science more “open,” but this has opened the gates to these purposeful agents of anti-science, with their “gaslight journals,” “gaslight science,” and “sophistry science,” as I’ll call it — loading up a dubious argument with a ton of references to make it look like it’s a massive source of consensus.

The challenge is that we don’t have a unifying political movement like MAHA behind us. Reality is messy, unreality is theater. They have theater on their side. They can choose the script, act it out, and drive emotional reactions. Get a protagonist, an antagonist, an injustice or a MacGuffin, and write your script. As a dramatist, you have no accountability beyond being entertaining and firing people’s dopamine receptors or adrenal glands.

That’s their goal. Professional journalism, actual science, and reality-based claims reports don’t have theater on their side. Add to this a fragmented media space with a major portion of it carved off from experts, and there’s a real long-term challenge ahead.

“Open” does not help us in this world. Closing science’s doors to transgressives might help. That means more stringent certification rules for journals, stricter claims assessments, and probably less science published — but better science, and aimed at scientists, not the public.

This way, people who aim science at the public will be seen more clearly as the propagandists and charlatans they are.

We Have a New Podcast — All Audio Now

Subscribe today via your favorite podcast app: