Preprints In Clinical Support Tools

Three POC tools now cite Covid preprints, adding value — but execution needs work

I’ve spent a lot of time documenting the issues and problems with current approaches to biomedical preprints — phantom commercial preprints, abandoned preprints, misleading preprints, public misperceptions of preprints, journalistic overreach via preprints, and preprints as misinformation.

I’ve also proposed a number of changes that could make preprints work, with the most important being to keep preprints circulating mainly among qualified individuals in some manner. Other improvements would include not adding DOIs, and retiring preprints after 6-12 months if they never pass peer review (or are never submitted to peer review). Finally, preprints that are supplanted by a final peer-reviewed paper should also be removed from other servers to avoid confusion.

All of this has been what Jaron Lanier calls “optimistic criticism” — offering criticism in the hopes that addressing the identified shortcomings could make something better. Improvement basically means minimizing harm while maximizing good. We don’t need the bad stuff about Facebook, cars, or preprints for these things to exist — instead, we’d like a Facebook without trolls and liars; cars that don’t pollute or contribute to global warming; and, preprints that benefit people without exhausting or misleading them.

Recently, a reader let me know that preprints have been appearing in clinical support and point-of-care (POC) tools like UpToDate, BMJ Best Practice, and ClinicalKey.

Was this another problem with preprints, too?

These workflow solutions started to incorporate preprints into their clinical overviews and evidence bases as Covid-19 emerged. (Another such offering, EBSCO’s DynaMed, doesn’t appear to cite preprints.)

But because this approach to preprints involves trusted intermediaries, expert selection, strong filtering for professional use, and relevant distribution, it seems to work — a finding that underscores how preprinting practices could be dramatically improved with some revised policies.

Because these are “early days” for these systems and how they integrate preprints, there are execution problems, as these systems don’t seem quite up to the task of dealing with rapidly incorporating information . . . yet.

Disclaimers on three preprint servers cited in the samples from these sources appear to frown on clinical use, which suggests to me that the servers’ open structure and profligate acceptance and distribution practices make a sweeping disclaimer necessary, but unhelpful — workflow tools driven by expert intermediaries seem to be valid users of a limited number of strong preprints. Such disclaimers wouldn’t be necessary if the distribution approach to preprints were limited to qualified readers and expert intermediaries of various kinds:

MedRxiv

BioRxiv

ResearchSquare

(Note that SSRN — which also has preprints cited in these clinical support tools — does not have a similar notice I could locate.)

Physicians seem to be finding a few preprints — selected for inclusion by editorial teams at UpToDate and others — to be solid, useful, and a good way to stay on top of the rapidly changing landscape of Covid-19.

It also suggests that preprinting is relatively low-yield when it comes to meaningful clinical information.

Preprints have a traditional role in systematic reviews and evidence-based medicine, but a role that is necessarily limited and tertiary. They are viewed by practitioners of these approaches to the literature in much the same way as conference proceedings, posters, and personal correspondence — necessary for as comprehensive a view as possible, but not centerpieces. Again, broad public accessibility isn’t necessary for these expert intermediaries to include them in synthesized overviews.

I discussed the value of preprints in these POC tools with a busy emergency physician in the Boston area who uses UpToDate regularly to help him with what he calls “the binomial decisions of emergency medicine” — broken or not, cardiac or not, etc.

For him, the inclusion of preprints in these workflow tools is the only way he discovers preprinted research — he doesn’t think anyone in clinical medicine seeks preprints out, but rather has to have them pushed to them through a trusted intermediary of some sort.

He never saw preprints in UpToDate until Covid-19, and a few that have been surfaced have been useful. In a handful of cases, the selections in UpToDate have helped him care for his patients better the next day (dexamethasone, proning). I’m sure users of some of the other POC tools are having similar experiences with the few preprints that are selected for inclusion. However, he is also careful to attenuate these inputs with multiple other inputs, conversations with colleagues, basic risk:benefit calculations, and his own deep clinical experience. He sees preprints out to the public as questionable in motivation and value — there aren’t that many useful ones, and there are outright abuses.

How preprints are included in these systems is a bit underdeveloped. Some of the preprints have gone unreviewed since early 2020, suggesting they are not passing muster more broadly and their inclusion may need to be reviewed. Some references point to preprints that now have published journal counterparts, but the references have not been updated to reflect the available peer-reviewed version. Many references to preprints don’t link at all.

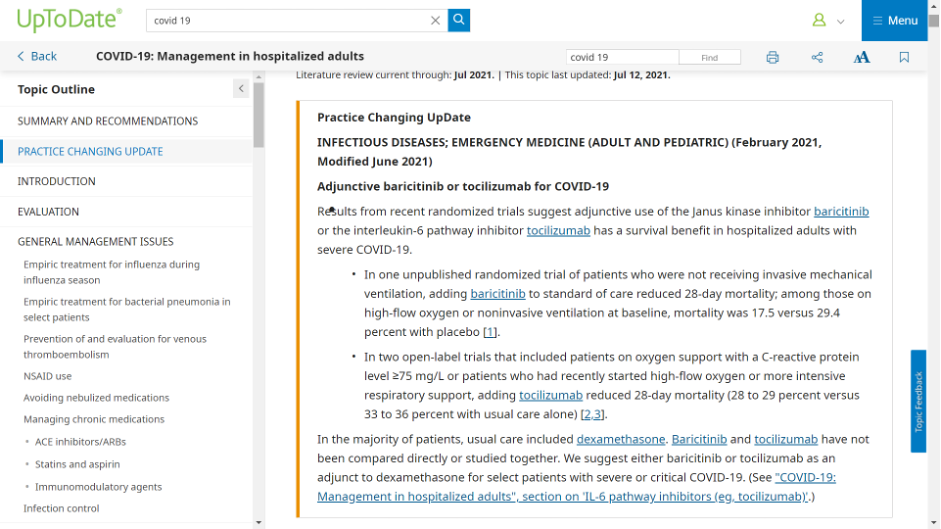

At UpToDate, there are instances of preprints being cited in what they call a “Practice Changing Update”:

In the sample I was able to obtain from UpToDate, two of 20 preprints included in Covid-19 entries have a peer-reviewed publication result so far. In those two instances, UpToDate cited the preprint and not the peer-reviewed version, despite the peer-reviewed version having been published months before the update released. Notoriously long periods between releases remain challenges for those working on these clinical support tools, as the editorial teams are diffuse and often deeply involved in clinical practice themselves.

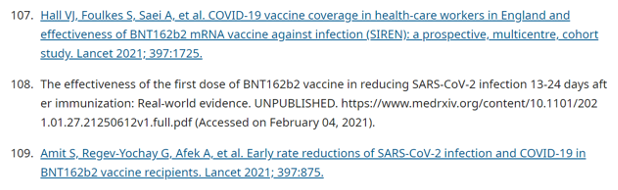

Here are a few examples (peer-reviewed VoRs are identified when they exist):

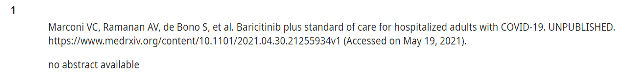

1 — preprint posted in January 2021, not linked

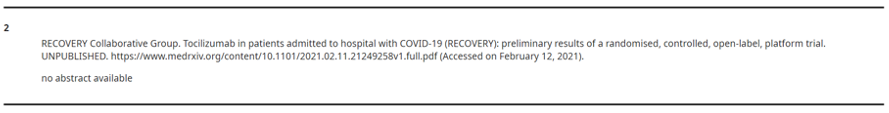

2 — preprint posted in February 2021, not linked; peer-reviewed version with dramatically different abstract and conclusions published in June 2021

3 — preprint posted in February 2021, not linked; peer-reviewed version published in May 2021

4 — preprint posted in May 2021, not linked

Notice that none of these have active links so that users can click over to see the cited source.

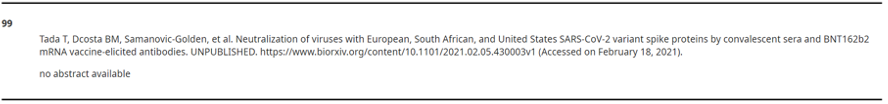

In BMJ Best Practice, more than 20 of the references in its publicly available Covid-19 resource cite preprints from medRxiv, bioRxiv, SSRN, or Research Square (listed by rate of occurrence). This example of preprint inclusion is more questionable, as this is a public document, and how readers are supposed to think about such preliminary reports — despite them being flagged with “(preprint)” — isn’t explained.

In some cases, linking to the preprint is impossible for readers of the BMJ Best Practice document — the SSRN preprint cited results in an error page, for instance. Many of the references point to outdated versions of the preprint in question. Some references point to PMC as the source of the preprint. One points to a preprint posted the day an article was accepted, but not to the peer-reviewed version, which was published just 10 days later — and more than six months ago at this point.

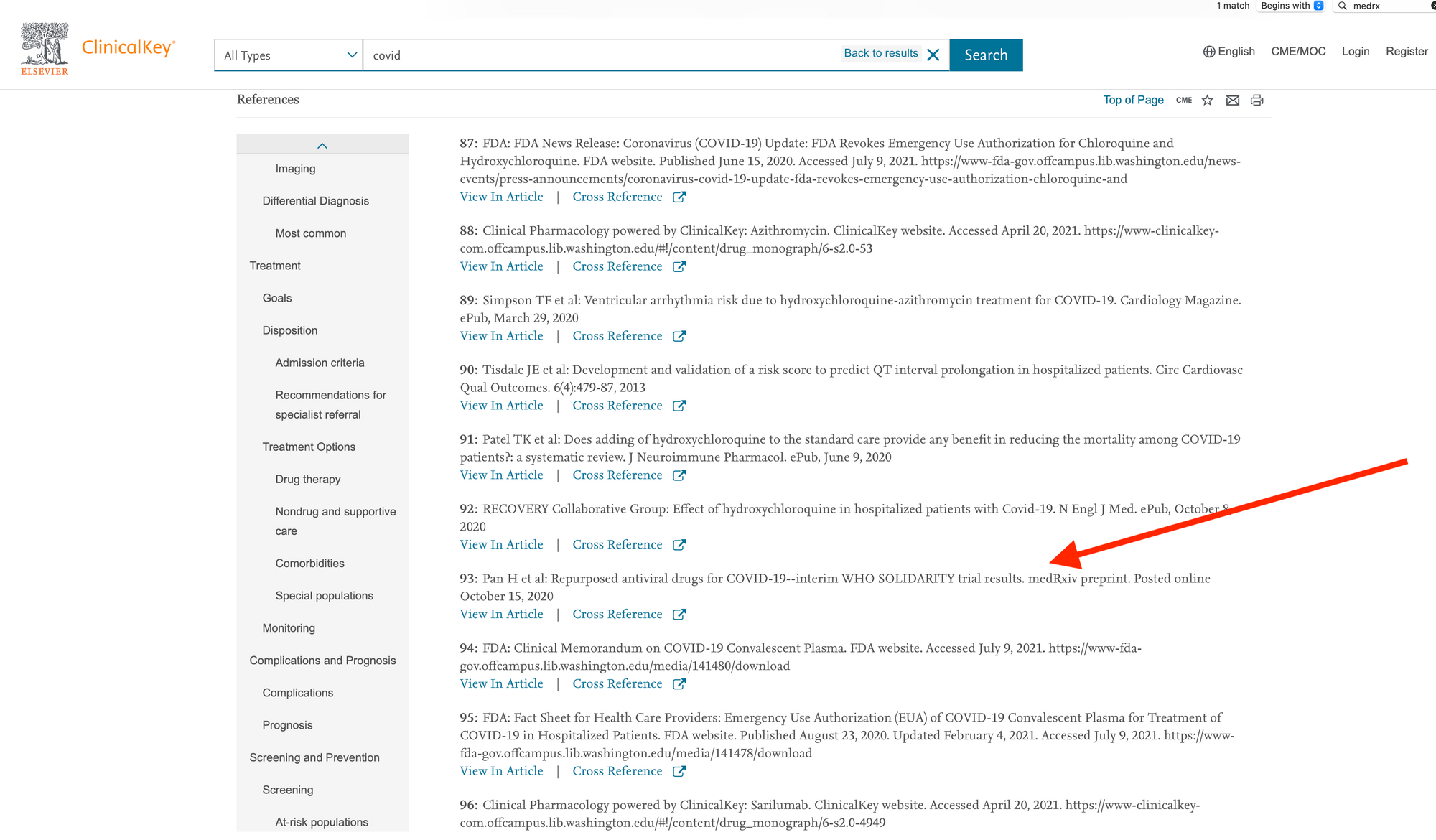

ClinicalKey cites a preprint in its article entitled, “Coronavirus: Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection”:

The authoritative version of the article cited here was published in NEJM on December 2, 2020, just about six weeks after the preprint was posted, and less than four weeks after it appears to have been submitted (judging by disclosure filings). The reference in ClinicalKey has not been updated in the intervening months, despite the NEJM article being freely available. (It’s also worth noting that this is a negative/null trial — the drugs in question delivered no discernible clinical benefits.)

As was the case before the idea of scale and servers took over, biomedical preprints can be useful if their distribution is limited to professionals via professional channels. In speaking with other physicians, it’s clear they don’t go searching for preprints, but have them surfaced in various ways by professional colleagues and other trusted intermediaries. They’re wary of those in the press, as well.

While the Covid pandemic has a pace and scope that makes this somewhat feasible, the approach will be difficult to scale for these resources without a lot more automation — editors are already stretched, and the review teams are small. At BMJ Best Practice, three authors and three peer reviewers were responsible for generating a Covid-related resource that includes more than 1,200 references.

Clinical databases, decision-support tools, and POC tools like UpToDate or BMJ Best Practice may also get strong pushback from journals if they decided to broaden their approach to becoming the upstream trusted intermediaries in medicine by leveraging preprints. But maybe not. Journals have not exactly been standing up to some changes that look like “the camel’s nose under the tent flap” — preprints, especially. With journalists having a 50-year documented record of attempting to supplant journals, and the rules that kept them at bay having been deeply eroded over the past decade, the time may be ripe for journalists and clinical workflow tools to leverage preprints to nudge ahead of the journals as biomedical newsmakers.

But it’s more likely this is a time-limited exigency for these POC tools, with the editors of UpToDate, BMJ Best Practice, and Clinical Key pulling back gradually, and returning to their traditional lanes and relationships.

Still, it’s a good example that preprints can work when there is a trusted intermediary and a strong set of incentives for quality interposed between the flood of papers and the user. The preprint servers don’t appear to be up to the task, as the low yield here demonstrates.

One big question is, Who will be that trusted intermediary in the future?