Is It Proper to Have a Lobbying Firm Employee on an NIH Search Committee?

The current search committee for the new NCBI Director includes an employee of a political lobbying organization

The current search for a new Director of the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) includes on its Search Committee an employee of a lobbying entity (with a for-profit parent), someone who also leads an advocacy project within that lobbying firm.

Is this appropriate?

Judging from emails obtained via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, questions of propriety, influence, and ethics fairly emerge around the NCBI’s current search for a new Director.

Background

New Venture Fund (NVF) is a registered lobbying organization that has been described as a “dark money” political fundraising machine. Created in the wake of Citizens United, it is a non-profit affiliated with Arabella Advisors, a consultancy specializing in advising philanthropies. NVF has revenues of over $500 million alone, and OpenSecrets.org notes that NVF “has fiscally sponsored at least 80 groups and acted as a pass-through agency funneling millions of dollars in grants for wealthy donors to opaque groups with minimal disclosure.”

Arabella’s network of political non-profits — NVF, the Sixteen Thirty Fund, the Hopewell Fund, and the Windward Fund — spent $1.2 billion during the 2020 US national elections.

Arabella Advisors, the for-profit consultancy that runs this network of political organizations, collects fees from fiscally sponsored projects within these. In 2020, these fees amounted to more than $46 million in revenues to Arabella.

SPARC is a project within NVF, via a fiscal sponsorship arrangement. Support includes the kind of infrastructure you’d expect — systems, shared functions like HR and finance. NVF, Arabella Advisors, and SPARC have shared the same address multiple times, even during election years.

In addition to political fundraising by its fiscal sponsor, SPARC runs the Open Research Funders Group (ORFG), which raises money on its behalf and funnels this back to SPARC, and ultimately through fees to NVF and Arabella Advisors. Neither SPARC or ORFG are non-profits, limiting the amount of disclosure they provide. Only NVF is a non-profit, but one functioning inside a for-profit and generating revenues via political fundraising and fees derived from fiscal sponsorship arrangements.

Heather Joseph, the Executive Director of SPARC, is an employee of NVF. SPARC is an entity Joseph may, in a sense, own, as she has, by all appearances, contracted with NVF individually to form SPARC, making it (which spawned ORFG and OA.Works) akin to a multi-faceted solo venture under her individual control, despite the window dressing of a steering committee.

The NCBI has had an acting Director since April 29, 2020, when James Ostell departed. In 2017, Ostell replaced David Lipman, who helped found NCBI in 1988. Lipman left NCBI in 2017 to become Chief Science Officer of Impossible Foods with his friend Pat Brown, an early proponent of OA publishing. In 2013, Lipman was involved in a scandal involving eLife, an OA journal launched within Wellcome Trust’s ambit and first published on PubMed Central, in violation of multiple policies and practices.

The Search Committee

To find a permanent Director, the NCBI formed a Steering Committee and posted a job description. Search committees generally consist of employees of the hiring organization, and rarely involve outside consultants or advisors. Even then, any outsiders would normally be vetted for conflicts of interest. This is relevant, as Joseph has not been forthcoming about these in the past.

Candidates for the NCBI Director job could apply through April 23, 2022.

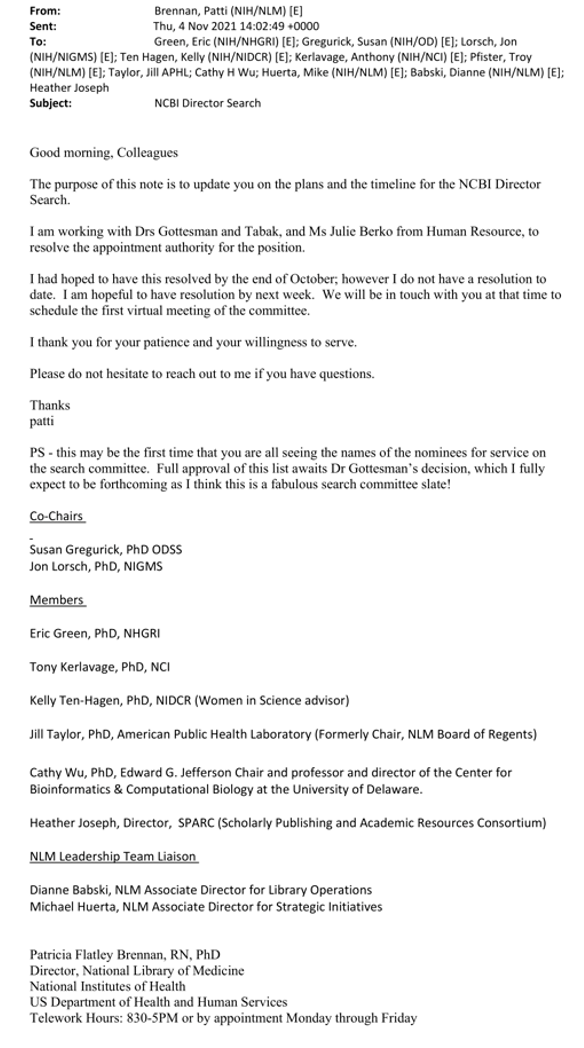

The NCBI Director’s Search Committee was outlined in an email sent November 4, 2021, which was obtained via the aforementioned FOIA request:

I wrote to Patti Brennan last Thursday evening to confirm that this was the search committee for the NCBI Director search. Receiving no response, I wrote again Saturday morning, and again this morning. She has not responded as of this posting, despite ostensibly having had three opportunities to correct or refute this list of Steering Committee members.

[UPDATE (12:05 PM ET): The NLM Communications Team has confirmed this is an accurate list of appointed members.]

I also wrote to Joseph this morning to confirm, and have not heard back.

To provide some more specifics on the individuals in the email and their jobs:

- “Dr. Gottesman” is Michael Gottesman, MD, Deputy Director for Intramural Research at the NIH.

- Susan K. Gregurick, PhD, is Associate Director for Data Science and Director of the Office of Data Science Strategy (ODSS).

- Jon R. Lorsch, PhD, is Director of the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS).

- Eric Green, MD, PhD, is the Director of the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI).

- Tony Kerlevage, PhD, is the Director of the Center for Biomedical Informatics & Information Technology in the National Cancer Institute.

- Kelly Ten Hagen, PhD, is a Senior Investigator in the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research.

- Jill Taylor, PhD, is a Senior Advisor for Scientific Affairs at the Association of Public Health Laboratories.

- Cathy Wu, PhD, is Director, Center for Bioinformatics & Computational Biology at the University of Delaware.

- Heather Joseph, is Executive Director of SPARC, and an employee of NVF.

Others included in the email are its sender Patti Brennan, RN, PhD, Director of the NLM; Mike Huerta, PhD, Director of the Office of Strategic Initiatives and Associate Director of NLM; “Tabak” is Lawrence Tabak, DDS, PhD, Acting Director of the NIH; and, Dianne Babski, Associate Director of Library Operations.

Joseph is the only member of the Search Committee without any affiliation to the NIH or academic credentials relevant to NCBI. She is the only member who works for a lobbying organization, and the only with ties to a for-profit entity.

It’s not abnormal for a search committee to draw some members from various stakeholder groups. When this is done, it’s usual and customary to have representation that is broad and representative. In this case, I can easily imagine a technology expert (cloud, AI/ML, security), a journal editor, a researcher from a large lab, and a publisher on the same committee — if representation were the goal. However, in this case, one of these things is not like the others, leading us to wonder how this might have come to be.

How Did This Happen?

Lobbyists and government employees are supposed to follow rules about disclosures and modes of contact. Allowing an employee of a lobbying organization onto the Search Committee for a Director-level position inside the NIH seems to cross some ethical and optical boundaries.

The tranche of emails obtained via the FOIA request reveals a cozy relationship between employees at the NLM/NIH and SPARC. There’s potentially nothing wrong with this, of course, except when those responsible begin giving too much authority away, are influenced disproportionately, or allow improper roles to be assumed.

For example, there are instances of the NLM and SPARC collaborating on articles and letters, but it’s not clear whether there was anything improper going on. There is an awareness that SPARC is asking a great deal from the NLM, with an offer to pay for the work being requested at one point.

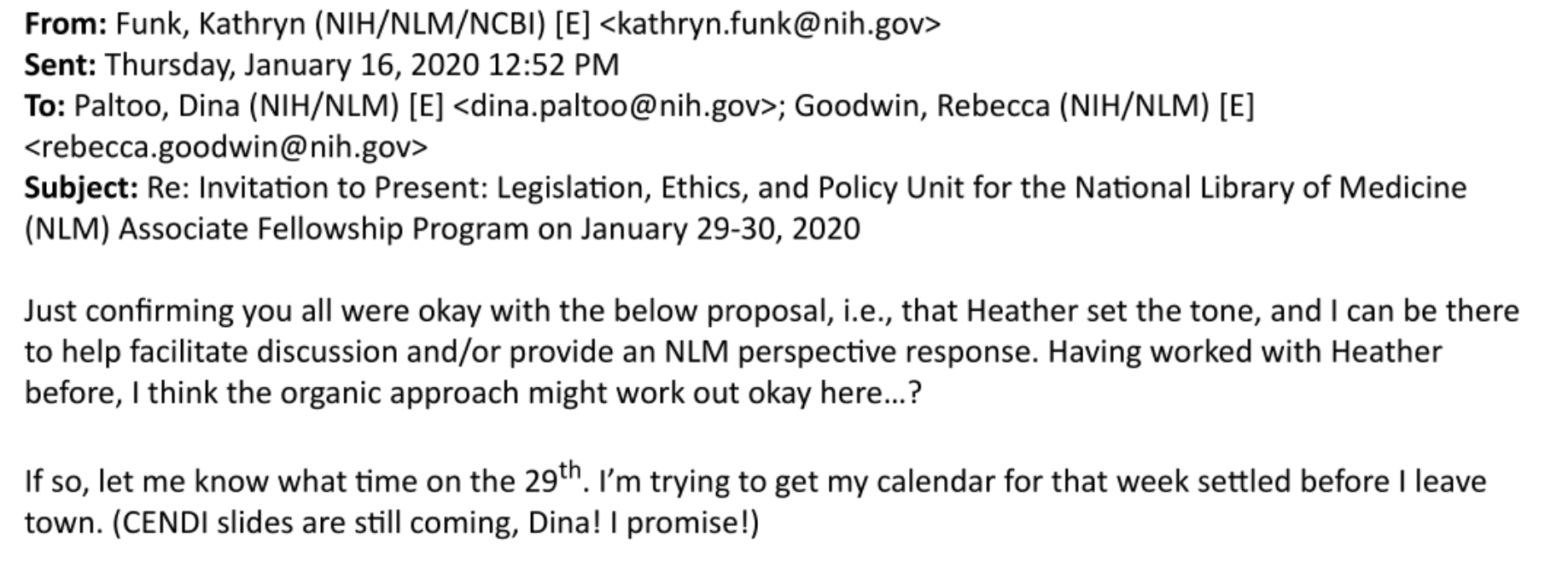

There is evidence of NLM employees’ deferring to SPARC on more than one occasion. For example, at one point, Kathryn Funk, a Program Manager for PubMed Central, emailed two other NIH employees about an NLM Associate Fellowship Program on January 29-30, 2020:

This appears to have been allowed, with the NLM program turned over to Joseph to “set the tone” while the NLM staff person took a backseat.

Again, this is an employee of a registered lobbying firm being given carte blanche to run an NIH/NLM program and “set the tone.”

Which brings us back to the bigger questions here — why and how was an employee of a political lobbying firm placed on a Search Committee of the NLM to help select a new Director-level appointee?

It seems possible that NLM/NIH employees have never understood SPARC’s relationship to NVF and Arabella Advisors. It has been difficult to unpack, and SPARC has never been forthcoming, failing to answer questions repeatedly despite acting as an advocate of openness and transparency. SPARC, OA.Works, and ORFG have portrayed themselves at various times as non-profits, a coalition, and in other “white hat” ways to elide the fact that they are fiscally sponsored by a political fundraising entity and that Joseph is both an employee and SPARC’s sole contract holder.

After reviewing years of emails between Joseph and NLM/NCBI staff — the FOIA request covered 5 years — as well as minuted meetings from the PMC National Advisory Committee (NAC) from 2008-2015 (the PMC NAC was disbanded in 2018), Joseph has been a consistent presence and effectively insinuated herself and other OA advocates into the NLM culture, blurring lines of authority and propriety.

Taken together, these may be all the explanation necessary.

Why It Matters

Search Committees can have a long-term impact on organizations and their strategic direction. The candidate they select may serve for years, if not decades, in the role, influencing the direction of the organization they run and the broader culture of the overall entity, in this case the NLM and ultimately the NIH. The effects of choices here can be profound and long-lasting.

Search Committee members have an opportunity to screen out individuals who may not share their views of the future for the organization, to ask questions that establish their priorities with any finalists, and to gain agreement about strategic direction in subtle ways. For instance, Joseph could smuggle in SPARC priorities to make NCBI a large-scale papers repository, or to heighten its activism as a voice for OA and open science.

The more subtle effect has to do with screening out candidates who may have views about NCBI that don’t comport with SPARC’s preferences and priorities. For instance, there are well-qualified people in the community alarmed at how PubMed and MEDLINE have been downgraded as strong indexing tools because NCBI has shifted — against its own policies — into becoming a publisher of full-text articles, while also indexing OA preferentially, even to the point of indexing content that is not peer-reviewed (preprints) or laced with conspiracy theories. It seems perfectly reasonable to assume one or more qualified candidates may want to develop stricter inclusion rules and cultivate higher standards. However, with Joseph on the Search Committee (and in a position of influence inside NLM generally), it’s less likely anyone possessing such views could advance.

Having an employee of a registered lobbying firm on a governmental Search Committee looks bad, and the fact that NLM and NIH didn’t realize this is worrisome, and may indicate a lack of ethical boundaries on both sides.

What level of transparency has NLM/NIH required here? Was Joseph asked to disclose her ties to NVF, both structurally (via fiscal sponsorship of SPARC) and individually (via contract and pay stub)? Was she required to disclose her ties to the Arcadia Fund, and its ties to SPARC? There is no record of any email requesting information about these ties, yet the FOIA search parameters (keywords, timeframe) could have reasonably been expected to catch such things if they came up in the context of the Search Committee.

Governance of conflicts of interest and political operatives disguised as do-gooders has been a long-standing problem at the NLM, with the other glaring example how the PubMed Central (PMC) National Advisory Committee (NAC) was too friendly with Wellcome Trust employees and advisors, which ultimately led to their improper conduct regarding a Wellcome Trust-funded journal, eLife.

This signals that NLM may have lost track of its objectivity, another theme from the tranche of emails, as there are now librarians with titles explicitly stating their role in advocating open science, developing programs pushing OA, and working closely with various OA-related firms (OA.Works, Unpaywall, Gate Foundation).

Having a role on a search committee can grant influence over decisions about NLM or NCBI policies, resource allocations, or privileges. People involved on hiring panels can use their “I was there when you were hired” card at various junctures as a way to exert influence. This would presumably come more naturally to a practiced policy advocate and employee of a lobbying firm.

Conclusion

The Search Committee for the new Director of the NCBI has an employee of a political lobbying organization on it, and a long-standing problem with influence from outside groups. The current situation may determine in subtle and obvious ways that the future direction of NCBI comports with the advocacy positions of SPARC.

Supporting independent inquiry and thought is more important than ever — to hold those in power accountable, to inquire with specialist knowledge, to know where to look, and to understand context. Please subscribe today. Thank you.